EPA Made No Commitment To a Specific Numeric Standard

EPA Inserted A Poison Pill In A Footnote

NJ DEP Variance Loophole Lets NJ Polluters Off The Hook & Undermines Benefits

The new requirements to incorporate WQS variance provisions will allow the Department to adopt temporary in-stream criteria or effluent conditions that will provide significant economic relief to permittees facing currently unattainable SWQS. ~~~~ NJ DEP “variance” @page 51)

NJ Spotlight reports today that EPA granted a petition by environmental groups to upgrade water quality standards for dissolved oxygen in the Delaware River to protect endangered sturgeon, see:

The Environmental Protection Agency announced Thursday it will raise a key water-quality standard for an urban stretch of the Delaware River Estuary between Trenton and Wilmington, DE, giving a big — and unexpected — victory to environmental groups that had long-sought the increase.

Environmentalists should not be spiking the ball quite yet. The EPA decision is not the “big win” they think it is.

The fine print once again shows how polluters and their friendly regulators are playing the long game, are two steps ahead of, and have once again outflanked the environmental groups.

The cliff notes version of the regulatory story (i.e. the long game) is that once the final EPA and/or DRBC water quality standard is actually adopted, it is implemented in State pollution discharge permit programs, not by EPA or DRBC.

The NJ DEP has already laid the regulatory foundation of that long game in a July 5, 2022 proposal of a “variance” from water quality standards. We drilled down and explained that in these posts:

The DEP makes it very clear that a variance is designed to provide “regulatory relief” to avoid the costs of compliance with water quality standards:

A permittee requesting a WQS variance must justify and demonstrate to the satisfaction of the Department that the SWQS …. would result in substantial and widespread economic and social impact, as proposed at N.J.A.C. 7:9B-1.16(b)4. (proposal @ p. 27)

The Department anticipates that the WQS variance will be useful to address implementation challenges for situations when the water quality criterion for a substance or the designated use of a waterbody/waterbody segment(s) cannot be attained due to the lack of feasible treatment technologies, lack of analytical methods to measure the substance to the criterion thresholds, or the potential to cause widespread social and economic impact, if implemented. (proposal @ p.32)

The new requirements to incorporate WQS variance provisions will allow the Department to adopt temporary in-stream criteria or effluent conditions that will provide significant economic relief to permittees facing currently unattainable SWQS,(@page 51)

The EPA inserted a poison pill in their approval document that specifically links the EPA water quality standard to NJ DEP and other state water pollution control permit programs (NPDES) and DEP’s variance loophole.

The EPA gives this “variance” game away, as usual, in the very fine print of footnote #52 on page 10 of their approval document. Here is the poison pill (emphasis mine):

52 DRBC has not fully evaluated how that cost burden may be distributed across ratepayers, especially in underserved and overburdened communities. However, DRBC has provided a partial list of potential cost mitigation options, such as federal, state, and local assistance programs that, if awarded, adopted, or implemented, may help offset costs for low-income households or help utilities finance costs (see DRBC 2022: Social and Economic Factors Affecting the Attainment of Aquatic Life Uses in the Delaware River Estuary).

See footnote #26 for that document, curiously which is described as a “draft”:

26 Delaware River Basin Commission. 2022. Social and Economic Factors Affecting the Attainment of Aquatic Life Uses in the Delaware River Estuary. September 2022 Draft.

https://www.nj.gov/drbc/library/documents/AnalysisAttainability/SocialandEconomicFactors_DRAFTsept2022.pdf

The DRBC Social and Economic Factors document plays right into the NJ DEP variance loophole via the economic impacts analysis – which includes a “household affordability score” – to analyze economic costs that could trigger the DEP variance loophole standard, i.e.:

“result in substantial and widespread economic and social impact”

The DRBC explains the objectives of this study – which explicitly are the same as NJ DEP’s variance:

Included in the list of studies to be completed is an evaluation of the social and economic factors affecting the attainment of uses, as described in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) water quality standards regulations at 40 CFR 131.10(g)(1)-(6). That regulation describes the factors that a state may consider in developing a use attainability analysis, including if meeting a use would cause substantial and widespread economic and social impact. While a use attainability analysis is typically performed by a state seeking to remove a use, an action not considered by Resolution No. 2017-4, it is apparent that the Commissioners intended for DRBC to utilize that framework in evaluating the social and economic impact of new proposed uses and associated effluent limits. The goal of this evaluation is to provide information on the social and economic impact of possible alternative uses for consideration and deliberation in rulemaking.

DRBC’s social and economic impact analysis is based on EPA Guidance, so the other States would be seeking to exploit the same loophole as NJ’s variance:

Two primary guidance documents were utilized to implement the evaluation of social and economic factors affecting the attainment of uses. These were:

- • EPA. Proposed 2022 Clean Water Act Financial Capability Assessment Guidance. February 2022. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-02/2022-proposed-fca_feb- 2022.pdf

- EPA. 2021 Financial Capability Assessment Guidance (800B21001). January 2021. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-01/documents/2021_fca_guidance_- _january_13_2021_final_prepub.pdf.

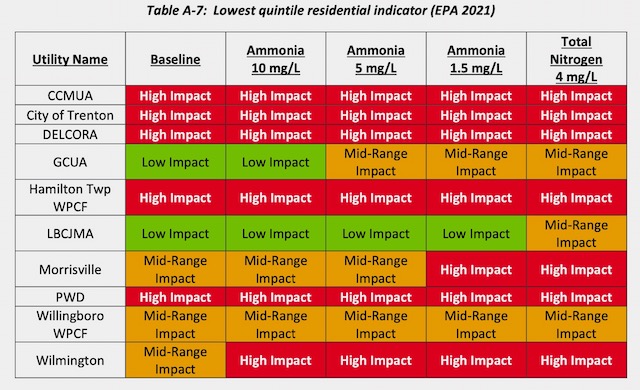

Here are the results, which suggest that there may be “substantial and widespread economic and social impact” that triggers the NJ DEP variance standard as well as US EPA’s variance relief standard – note that the NJ facilities are Trenton, Camden, Gloucester, Hamilton make up a significant fraction of the total pollution discharge to the Delaware River:

Finally, I m must note that the environmental group petition demanded that EPA adopt a minimum numeric dissolved oxygen standard of 6.3 mg/L:

To protect the “propagation” use, the EPA must also upgrade the dissolved oxygen (“D.O.”) criteria for the subject zones to at least 6.3 mg/L.

However, the EPA’ approval document does not make a commitment to that minimum 6.3 mg/L standard. EPA merely references a range of values identified in research. Here’s how EPA evaded support for a specific numeric standard:

For example, experimental tests on juvenile Atlantic sturgeon showed instantaneous growth declined 50% when dissolved oxygen decreased from 70% to 40% saturation at 20°C, which is equal to dissolved oxygen concentrations of 6.35 to 3.62 mg/L, respectively.34 At summer temperatures for the Delaware River Estuary (i.e., 28°C), juvenile Atlantic sturgeon did not grow when dissolved oxygen concentrations were at the currently applicable summer criterion of 3.5 mg/L. 35

Once again, EPA regulators have played the environmental groups.

EPA and/or DRBC may set a weaker standard than the minimum 6.3 mg/L, especially when cost considerations are injected into the political pushback from the polluters.

Finally, EPA found that 12 months was a realistic timeframe for DRBC to propose a water quality standard (which typically take a year more for adoption). But I could find no date certain EPA committed to to propose or adopt any federal EPA water quality standard.

Based on EPA’s regulatory track record, I strongly doubt that EPA will propose, no less adopt, a water quality standard in 12 months.

After EPA or DRBC adoption of that water quality standard, the States then implement the standards in their pollution discharge permit programs.

Typically, when a water quality standard is updated, DEP phases it in during renewal of POTW discharge permits (NJPDES). DEP does not “call” all permits along a stretch of river and updated them all at once. Depending on the timing of permit renewals, implementation of any new EPA or DRBC water quality standard in permits could take another 5-7 years.

Of course, the polluters will likely challenge those State discharge permits, both administratively and judicially, particularly to exploit NJ DEP’s variance loophole, based on “substantial and widespread economic and social impact”.

Those legal challenges will add several years more.

So, any actual improvement in Delaware River water quality is highly uncertain and a long way off.

I don’t expect news reporters to understand this regulatory complexity, but Maya van Rossum at Riverkeeper is an attorney and she surely does. Shame on her for exaggerating the benefits and not calling out DEP on their variance loophole and EPA for their games.