Turtle Law A Perfect Example of Everything That’s Wrong With NJ’s Conservation Community & Press Corps

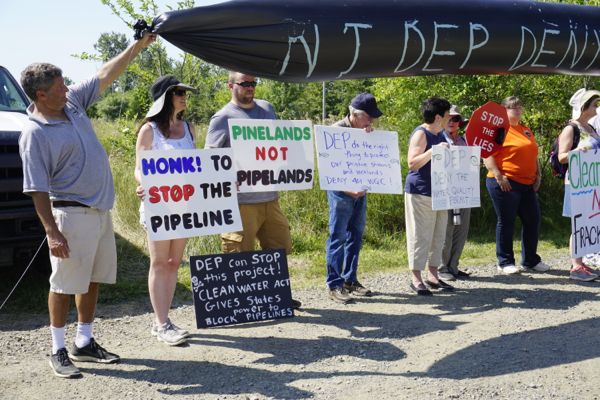

This is what weenie conservation looks like

(7/9/14) Taken on way to public hearing on DEP CAFRA rule proposal – see “Why Don’t We Do It In The Road”

Here is a perfect example of the worst aspects of troubling tendencies in the NJ Conservation community and media. This goes way beyond greenwash – another band aid on a gaping wound sold as progress.

Governor Christie, NJ conservation groups, legislators, and the media just congratulated themselves and celebrated passage of a law designed to protect diamondback terrapin. The law was described as a “key step for the species”.

The prohibition on harvesting the turtles will no doubt have a positive impact on the species. But a “key step”? Don’t think so.

However, glowing press reports and praise by conservationists – devoid of context – left the general public with a completely false and overly favorable assessment, while key issues were ignored.

The bill faced no opposition and was passed unanimously in both houses of the Legislature and signed by Governor Christie, NJ’s worst environmental governor.

Christie took the opportunity to issue an over the top press release:

“Today we join other Atlantic coastal states that have taken an important step to prevent this unique species from any further decline toward extinction. The diamondback terrapin is a natural treasure and integral part of our coastal landscape in New Jersey, and this action will help to ensure the species remains a feature of our natural landscape for generations to come,” said Governor Christie.

That is total bullshit – extinction is a distinct possibility and those extinction threats are greatly magnified in the “generations to come” – particularly as a result of the climate denial, coastal land use and fossil fuel dominated energy policies of Governor Christie.

And useful idiots said crap like this:

“It’s a good move,” said Bill Sheehan, director of the Hackensack Riverkeeper. “Now we just have to keep up with the poachers. It’s up to the proper agencies to enforce this.”

It’s not the poachers you need to worry about there Captain Bill.

Here is the real story you were not told that makes a mockery of what you were led to believe. I tried to use this same turtle species to suggest that story a few years ago (and this post and this post).

“Ghost Trees – evidence of sea level rise and storm surge impacts Jake’s Landing, Dennis Township, Cape May” – Source Rutgers CRSSA, Lathrop.

Primary Threats To Diamondback Terrapin

We learn from Defenders of Wildlife

Threats

The diamondback terrapin is threatened by habitat destruction, road construction (terrapins are common roadkill) and drowning in crab traps.

Climate change is also poised to bring major changes to the terrapin’s habitats and life cycle. By the end of this century, sea level is projected to rise between 2.25 feet under a low emissions scenario and up to 3.25 feet under the highest emissions scenario.

Due to land subsidence in the Northeast, the effect of the rise will seem about 10 to 20% higher than the actual. Salt water incursion into brackish tidal marshes will alter their character and potentially make large areas saltier than the terrapin can tolerate. Storm surges and beach erosion threaten their preferred nesting habitats. And higher temperatures on nesting beaches could skew the sex ratios of offspring.

Prohibition on harvesting turtles will have absolutely no impact on reducing the threats of climate change and habitat destruction.

Actual Conditions and Status of Threats

I recently wrote to document a range of devastating climate change impacts on the NJ shore – including rampant overdevelopment.

Here is an excerpt that is directly relevant to the diamondback terrapin, from NJ DEP’s Coastal Assessment and Strategy – 2016-2020: (@ page IV-115)

Tidal marshes can adapt and keep pace with sea level rise through vertical accretion and inland migration, but must remain at the same elevation relative to the tidal range and have a stable source of sediment. Coastal wetlands risk permanent inundation if sea levels rise faster than the rate by which they can accrete. Through the process of vertical accretion of sediment and organic matter, the tidal salt marsh surface will rise in relation to sea level, i.e., the marsh can continue to grow ‘up’ into a rising sea (Cahoon 2010). When sea level rises faster than marsh accretion, tidal marshes are drowned and replaced by unconsolidated shore (i.e., mud or sand flat) and eventually open water (Cahoon and Guntenspergen, 2010). The degree of wetland loss is directly related to the rate of sea level rise compared to the accretion rate. The combination of sea level rise and vertical accretion forces coastal wetlands to migrate inland causing upslope transitional brackish wetlands to convert to saline marshes and the saline marshes on the coastline to drown or erode.57

Along portions of New Jersey’s coast, development located upland of the marsh edge forms a physical barrier to the gradual movement of marshlands inland, blocking the inland migration of these ecosystems as sea level rises. One concern along New Jersey’s coast is that rising sea level will reduce the extent of some coastal marshes, changing them from vegetated areas to mud flats or open waters and that upland development will prevent the migration of tidal wetlands landward, resulting in an overall reduction of the extent of these vital components of the coastal ecosystem.

In a study from July, 2014, Modeling the Fate of New Jersey’s Salt Marshes Under Future Sea Level Rise, conducted by the Rutgers University Center for Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis, modeling results suggests that if sea level rises between one to two feet by 2050, existing tidal salt marsh in New Jersey could decline by approximately 5%, being replaced by open water and unconsolidated shore. One foot of sea level rise may cause more than 9,300 acres of salt marsh to convert to open water and nearly 2,000 acres of salt marsh could be impeded from retreat. The modeling also found that at a sea level rise of three feet or greater, salt marshes are not able to vertically accrete fast enough, increasing the loss and conversion of salt marsh. While the predicted loss may be balanced by ‘new’ marsh (i.e., unimpeded marsh retreat zone) it is unclear whether this ‘new’ marsh will have the same ecological value in the short-term (i.e. over decadal time scales) as the established tidal salt marshes that may be lost.

New Jersey’s coastal wetlands on the Atlantic Coast are bordered by roads and extensive development. This hard infrastructure provides little or no natural buffer to our coastal wetlands. Adequate low elevation natural land cover buffers may allow coastal wetlands to migrate landward over time as sea level rises. Coastal buffers may also provide much-needed sediment required for coastal marsh elevations to rise with the rising sea level over time. The combination of sea level rise and vertical accretion forces coastal wetlands to migrate inland causing upslope transitional brackish wetlands to convert to saline marshes, and the saline marshes on the coastline to drown or erode. Along portions of New Jersey’s coast, development located upland of the marsh edge forms a physical barrier to the gradual movement of marshlands inland, blocking the inland migration of these ecosystems as sea level rises. Further, because the State’s Freshwater Wetlands Protection Act allows buffers to range in size from zero, in some cases, to 150 feet maximum, there has been an inclination to match, but not exceed, these buffer widths for coastal wetlands. As a result, over time, the width of buffers adjacent to coastal wetlands has declined.

Delaware Estuary Threats

Turtle habitat includes the Delaware estuary, which DEP documents is also threatened: (page IV-74)

The Delaware Estuary is also experiencing climate change-related issues such as the inability of wetlands to keep pace with sea level rise due to the lack of sediment; the impacts of sea level rise on wetlands health and extent; land subsidence; and the migration of alien or invasive species into wetlands. The estuary also has water quality issues due to runoff, development, and industrial discharges.

Subsidence Threats

In addition to climate change driven coastal marsh and Delaware threats, the NJ Coastal plan is also subsiding (sinking): (page IV-114)

To understand how salt marshes drown or expand, we need to have an understanding of the balance between sediment supply, sea level rise, and vegetation. If the marsh platform evolves to an elevation lower than mean high tide, either through reduced sedimentation, land subsidence, or an increased rate of sea level rise, then these marsh plants will die and the marsh will drown. Drowning often results in a rapid loss of marsh elevation; once marsh plants die, the marsh sediments become susceptible to erosion, and marshes rapidly convert to subtidal flats (e.g., Fagherazzi et al., 2006)51.

Residents of New Jersey’s coastal zone can see and note changes to the marsh edge. As Downe Township Deputy Mayor Lisa Garrison noted in a recent article, “Erosion is changing the face of the meadows.” A recent study in New Jersey found interior marsh (i.e. marsh platform) loss from expanding channel networks and pond development is causing significant dissection of the marsh platform.52 The researchers noted that the reduction in marsh habitat area has accelerated due to perimeter shore line erosion, sea-level rise, and coastal submergence. For example, along a marsh shoreline within the Mullica Great Bay estuary system, the researchers found that the rate of loss of saltmarsh habitat amounted to 1.6 m yr. between 1995 and 2008. As a means of reducing mosquito problems several organizations within the state developed and refined techniques for Open Marsh Water Management (OMWM). OMWM is a land management practice designed to control mosquitos by creating open water ponds on marsh or parallel grid ditching and salt hay farming to increase tidal exchange on the marsh.

The erosion of marsh edge and marsh platform can also result in an indirect impact to coastal shoreline development because marshes reduce storm surge wave heights due to their position in the coastal landscape and the plants growing on the surface. Severe erosion of the marsh edge results in a retreat of the marsh mat, thereby reducing the extent of the marsh.53 Several recent reviews (Gedan et al., 2011; Shepard et al., 2011; Spalding et al., 2013)545556 have found that salt marshes have a moderating influence on attenuating storm surge and waves and a moderately positive role in shoreline stabilization.