DEP Destroying Ability To Remove Pollution That Is Killing Barnegat Bay

Excavating Ponds and Digging Ditches Harms Wetlands Functions

When will the destructive mosquito control program be shut down by DEP?

Barry concluded that just as in 1927, people died because of cynical decisions made by shortsighted politicians drawing on bad science. ~~~ The Most Ambitious Environmental Lawsuit Ever (NY Times, 10/4/14)

The New York Times is running a must read story today about a lawsuit against the oil and gas industry for destroying the Gulf Of Mexico’s coastal wetlands systems that, among other things, protect New Orleans – read the whole thing: The Most Ambitious Environmental Lawsuit Ever.

The Times tells the all too typical story of politics, science and power: how the power of the oil & gas industry and political corruption combined to destroy coastal wetlands systems and undermine the State’s Coastal Management Plan and restoration program.

Basically, the canals dug by the oil & gas industry have vastly accelerated erosion and the industry has failed to comply with permits that require restoration to prevent that erosion.

There are strong parallels to NJ:

- the oil & gas industry virtually owns the state government and political apparatus

- the Governor has incredible power

- environmental groups never mounted a serious challenge to the development that is causing the problems

- natural coastal ecosystems were destroyed by unregulated industry greed

- Gov’s Bobby Jindal & Chris Christie share the same pro-corporate anti-regulatory ideology

The difference is that here in NJ, it’s the land development lobby that killed the coast, not the oil & gas industry (at least not directly – oil & gas are causing climate change that will destroy the coast eventually).

So, what does all this have to do with a NJ DEP mosquito control program?

While reading the Times story I was struck by a metaphor used to describe the process of erosion: industry dug canals serve as an ice pick on a melting block of ice.

While not remotely on the scale or severity of what is going on in the Gulf, a similar erosion process is underway in NJ’s coastal wetlands systems.

The primary threats involve destruction of wetlands by development, conversion & alteration of natural wetlands systems, and sea level rise & inundation.

But in this case, the problems are not caused by the developers or sea level rise or natural processes, but are caused by a DEP approved program.

One surprising facet of that coastal wetland erosion process was described in a recent research paper I read:

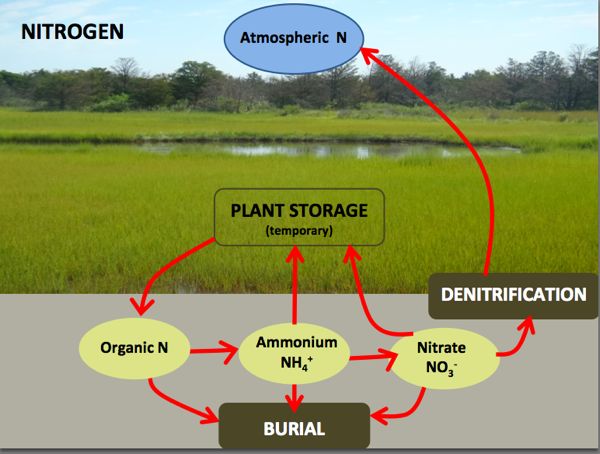

The environmental services provided by wetlands that fringe the coast are at risk from sea level rise. In this regard it is important to understand the current extent of services wetlands provide, such as nutrient cycling-retention, to better plan for the future and related environmental and land use changes. This was designed to enhance our understanding of the nitrogen uptake, burial and removal services provided by coastal wetlands in Barnegat Bay. By quantifying the proportion of the watershed’s nitrogen load that is processed by vegetation, buried, and most importantly, removed by microbial denitrification per unit area, resource managers and policy makers will have needed information to evaluate, protect and enhance wetlands, while maintaining benefits for water quality, as well as for wildlife habitat, water flow and biodiversity. The objective of the study is to help inform resource managers of the value of wetland-watershed linkages, understand nutrient sinks, and how sea level rise may alter these critical environmental services. […]

The objective of this study was to estimate the removal of dissolved nitrogen via denitrification in the tidal wetlands of Barnegat Bay. In addition, we compared these removal rates to burial rates and inputs to the Bay from a previous study.

The study is part of DEP’s Barnegat Bay research agenda, focusing on issues related to nutrient pollution.

It is well known that natural wetlands systems remove nitrogen from the system and thereby protect water quality:

But in reading the DEP sponsored study, I was surprised by a major finding that a DEP approved mosquito management program was having serious negative impacts on the structure and function of coastal wetlands systems, including a dramatic impact on their ability to reduce nitrogen loads to Barnegat Bay:

Open Marsh Water Management (OMWM), where interior vegetated marsh is converted to shallow ponds. Over 10,000 acres of salt marsh has been physically altered with OMWM in Barnegat Bay, thus making it important to measure the effect of OMWM ponds on denitrification. … Overall, salt marsh denitrification has the potential to remove approximately 13 to 33% of the incoming estimated N load entering the Bay (7.0 x 105 kg/yr). Both sediment burial and denitrification can sequester or remove between 91 and 111% of the incoming load. Tidal marshes within the Barnegat system are an important component of the ecosystem and help to remove a substantial amount of N entering the bay.

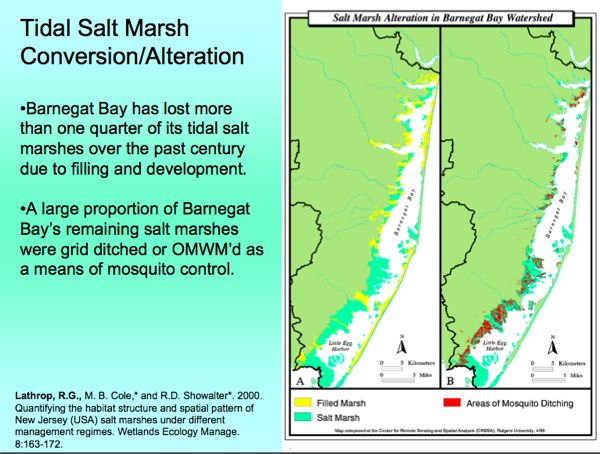

Salt marshes have a long history of management, such as diking, draining, salt hay farming, ditching, and more recently, Open Marsh Water Management (OMWM). OMWM has been adopted in several Atlantic coastal states to control mosquitoes by excavating ponds and connecting ditches (pond radials) on the marsh platform. While ponds are natural salt marsh features, OMWM increases the density of ponds across the marsh and places ponds in areas where natural ponds may not have formed. In addition, ponds may be established in areas that have been previously grid ditched (Figure 12). Grid ditching has reduced the occurrence of natural ponds (Adamowicz and Roman 2005), but the effects of creating ponds at a high density in areas previously grid ditched is unknown. The mosquito control commissions operating in Barnegat Bay have been applying OMWM since the 1970s. Ocean County Mosquito has installed over 9000 ponds across 12,000 acres in Barnegat Bay over the last ~30 years (OCM, per comm.). It is unclear how a high density of ponds in areas that were once vegetated marsh will affect N removal.

Denitrification rates were lower in the OMWM ponds (72±4 mol N m-2 hr-1) than the vegetated marsh sites (113±23 mol N m-2 hr-1 ,Table 6 and Figure 13) which were similar to control locations (102±19 mol N m-2 hr-1). [My Note: that is a 36% reduction in nitrogen removal rate]

- OMWM appears to lower the overall rate of denitrification during peak warm months. Anareal survey of the extent of OMWM and rates within these sub-systems needs to beundertaken to better determine the impact on the overall budget of N to the Bay.

These negative findings are consistent with a prior 2000 Rutgers CRSSA study: “Quantifying the habitat and spatial pattern of New Jersey (USA) salt marshes under different management regimes.”

The findings from that decade old 2000 study were presented to DEP in July 2010:

So, given these findings, when will the destructive mosquito control program be shut down by DEP?

[PS – and after DEP shuts down the physical destruction, maybe they can next stop the chemical warfare:

Pingback: serigrafia camisetas madrid baratas

Pingback: trikots aus england bestellen

Pingback: bayern trikots billig kaufen

Pingback: camiseta seleccion chilena 2012

Pingback: camisetas futbol americano baratas madrid

Pingback: liverpool third training jersey

Pingback: ray ban aviator sunglasses

Pingback: puma italien trikot damen

Pingback: camiseta oficial de juventus 2012

Pingback: maillot psg okocha

Pingback: colores de la nueva camiseta de la seleccion colombia

Pingback: borussia dortmund cl jersey

Pingback: ブランドスーパーコピー

Pingback: maillot mexique coupe du monde

Pingback: camiseta nueva de argentina

Pingback: camisa reebok internacional iii 2011

Pingback: trikot torwart deutschland

Pingback: christian louboutin Purple Heels

Pingback: socceroos jersey world cup 2014

Pingback: barcelona 3rd jersey 2015

Pingback: blue ray ban sunglasses

Pingback: belgium shirt burrda

Pingback: fitflop Chaussures

Pingback: liverpool fc new kit to buy

Pingback: camiseta oficial italia 2012

Pingback: donde comprar la camiseta original de la seleccion colombia para mujer

Pingback: fc bayern trachten trikot kaufen

Pingback: camiseta de francia 2013 precio

Pingback: zola chelsea shirt number

Pingback: schalke trikot gr??e l

Pingback: camisa inter oficial 2013

Pingback: matte black ray bans

Pingback: ajax home kit 12 13

Pingback: jag

Pingback: psg trikot zlatan

Pingback: barcelona trikot kaufen g锟斤拷nstig

Pingback: precio camiseta colombia 2014

Pingback: benfica trikot cardozo

Pingback: todas las camisetas del barcelona de la historia

Pingback: Snapback Hats Outlet

Pingback: wholesale nba jersey

Pingback: christian louboutin outlet store

Pingback: ajax 2014 away shirt

Pingback: ronaldo israel shirt

Pingback: duvetica down

Pingback: mario prada

Pingback: christian louboutin pigalle

Pingback: where to buy celine bags

Pingback: chelsea football kit age 11

Pingback: manchester city away kit 2013 14