Industrial Pollution Limits & Technology Not Updated Since the 1980’s

Given that millions of NJ residents drink water from rivers that receive industrial wastewater discharges, you might want to think about this next time you turn on your tap.

Last week, I focused on serious flaws in DEP regulations and permit programs, noting:

- DEP’s failure to ratchet down on industrial non-point water pollution;

- DEP’s failure to regulate greenhouse gas emissions;

- DEP’s failure to update standards and permits to reflect current science and data;

- DEP’s new enforcement priorities that stress voluntary “sustainable development”.

I forgot to mention that at the same time DEP enforcement priorities and staffing are shifting to “get more done with partnerships”, that DEP is almost 3 years behind in issuing the mandatory annual Report required by the Clean Water Enforcement Act (CWEA). (Why is there no legislative oversight or press scrutiny of that?)

But many of the same problems in DEP regulatory oversight are mirrored at the federal level at US EPA.

In response to my posts, a Washington DC colleague sent me a recent General Accounting Office (GAO) Report that makes similar observations, blasting US EPA’s industrial wastewater control program under the Clean Water Act.

According to beltway trade publication, Inside EPA, E&E Reporter:

EPA has failed to fully tackle industrial polluters — GAO

Annie Snider, E&E reporter

Published: Thursday, October 11, 2012

U.S. EPA likely has not been cracking down on industrial water pollution as hard as it should have, due to a flawed process for reviewing effluent guidelines, a government watchdog agency said yesterday.

The two-phase process EPA uses to decide which guidelines to review means the majority of industries never get an adequate look, according to a new Government Accountability Office report.

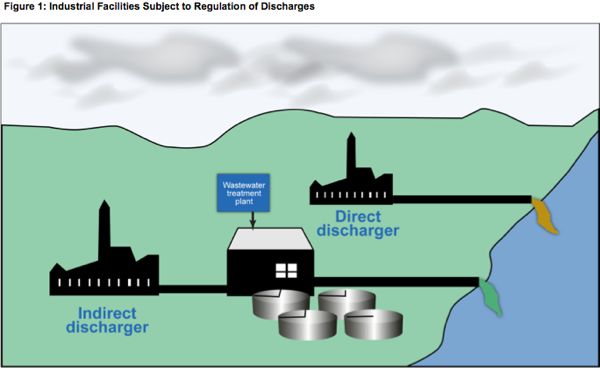

Under the Clean Water Act, EPA is supposed to annually review guidelines for pollutants being discharged from industrial facilities such as factories and wastewater treatment plants in order to decide whether new information about the pollutants’ dangers or about technologies available to decrease them warrants lower limits.

But most guidelines have not been updated since the 1980s or 1990s. Moreover, in recent years, EPA’s focus has shifted from point sources — such as the industrial facilities covered by these effluent guidelines — to nonpoint sources such as agricultural and urban runoff, which are now responsible for most pollution making its way into waterways. Staff levels for the effluent guidelines program have been cut 40 percent, EPA officials told GAO.

(sorry no link to the complete E&E Reporter story, it’s a subscription service – but you can read the full GAO Report – it provides an excellent background and history of the Clean Water Act’s industrial effluent program requirements and EPA’s implementation efforts).

GAO found a number of significant flaws, particularly regarding EPA failure to monitor pollution discharges, to update data or correct errors in industry data, to incorporate advances in treatment technology, and to ratchet down on industrial NPDES permits for discharges of toxic pollutants.

The Clean Water Act requires that these industrial pollution permits reflect “the best available control technology” and the EPA is required to review and upgrade these technologies annually. So these are massive and fundamental failures by EPA to properly regulate industrial dischargers, particularly some of the most toxic pollution.

The water pollution control permits (NJPDES) for many of these facilities are governed by the flawed industrial effluent guidelines targeted in the GAO Report. According to DEP’s most recent CWEA Report, DEP regulates 640 point source discharges to NJ waters.

Lax permit pollution limits and failure to update permits could explain the apparent contradiction I discussed last week: high permit compliance rates but declining environmental quality. As I noted, the answer to that is stricter permits and enforcement.

So NJ water quality and our drinking water are put at significant risk by these EPA and DEP regulatory failures.

Here are some of the more significant and troubling findings from the GAO Report:

EPA documents and some experts we contacted also stated that data collected in the Toxics Release Inventory are useful to identify toxic discharges. Nevertheless, according to the agency and experts, these inventory data have limitations that may cause EPA to either overestimate or underestimate the relative toxicity of particular industrial categories. The limitations they identified include the following:

Limitations in Hazard Data May Have Caused EPA to Overlook Industrial Categories

The two sources EPA relies on during its initial screening process— discharge monitoring reports and the Toxic Release Inventory—have limitations that may affect the agency’s ability to accurately rank industrial categories for further review on the basis of the human health and environmental hazards associated with those categories. Data from industrial facilities’ discharge monitoring reports have the benefit of being national in scope, according to EPA documents, but according to agency officials and some experts we spoke with, these data have several limitations that could lead the agency to underestimate the hazard caused by particular industries. Specifically:

• The reports contain data only for those pollutants that facilities’ permits require them to monitor. Under NPDES, states and EPA offices issue permits containing limits for pollutant discharges, but those permits may not include limits for all the pollutants that may be discharged, as for example, if those pollutants are not included in the relevant effluent guidelines or need not be limited for the facility to meet state water quality standards.30 If a pollutant is not identified in a permit, and hence not reported on discharge monitoring reports, it would not be part of EPA’s calculation of hazard and would not count toward the ranking of industrial categories.

- The reports do not include data from all permitted facilities. Specifically, EPA does not require the states to report monitoring results from direct dischargers classified as minor. According to EPA, the agency in 2010 analyzed data for approximately 15,000 minor facilities, or about 37 percent of the 40,500 minor facilities covered by NPDES permits. As a result, the pollutants discharged by the remaining 25,500 minor dischargers would not be counted as part of the relative toxicity rating and could contribute to undercounting of pollutants from those industrial categories. For example, most coal mining companies in Pennsylvania and West Virginia are considered minor dischargers whose pollutants would not count toward the ranking of that industrial category.

- The reports include very limited data characterizing indirect discharges from industrial facilities to wastewater treatment plants, according to EPA documents. Thus, the data do not fully document pollutants that, if not removed by a wastewater treatment plant, are discharged. These data are not incorporated into EPA’s calculations of hazard for each industrial category, and thus result in underestimated hazards.31 …

EPA documents and some experts we contacted also stated that data collected in the Toxics Release Inventory are useful to identify toxic discharges. Nevertheless, according to the agency and experts, these inventory data have limitations that may cause EPA to either overestimate or underestimate the relative toxicity of particular industrial categories. The limitations they identified include the following:

- The data reported are sometimes estimates and not actual monitored data. In some cases, the use of an estimate may overreport actual pollutant discharges. For example, some industry experts said that to be conservative and avoid possible liability, some facilities engaging in processes that produce particularly toxic pollutants, such as dioxin, may report the discharge of a small amount on the basis of an EPA- prescribed method for estimating such discharges even if the pollutant had not been actually monitored.

- Not all facilities are required to report to the inventory, which may lead to undercounting the discharges for the industrial categories of which the facilities are a part. Facilities with fewer than 10 employees are not required to report to the inventory, and neither are facilities that do not manufacture, import, process, or use more than a threshold amount of listed chemicals. For example, facilities that manufacture or process lead or dioxin do not need to report to the inventory unless the amount of chemical manufactured or processed reaches10 pounds for lead or 0.1 grams for dioxin. […]

In more than half of our interviews (10 of 17), experts told us that EPA should consider technology in its screening phase,38 and some of them suggested the following two approaches for obtaining this information:

- Stakeholder outreach. Experts suggested that key stakeholders could provide information on technology earlier in the screening process. Currently, EPA solicits views and information from stakeholders during public comment periods following issuance of preliminary and final effluent guidelines plans. According to experts, EPA could obtain up-to-date information and data from stakeholders beyond these formal comment periods. For example, EPA officials could (1) attend annual workshops and conferences hosted by industries and associations, such as engineering associations, or host their own expert panels to learn about new treatment technologies and (2) work with industrial research and development institutes to learn about efforts to reduce wastewater pollution through production changes or treatment technologies.

- NPDES permits and related documentation. Experts suggested that to find more information on treatment technologies available for specific pollutants, EPA could make better use of information in NPDES permit documentation. For example, when applying for NPDES permits, facilities must describe which pollutants they will be discharging and what treatment processes they will use to mitigate these discharges. Such information could help EPA officials administering the effluent guidelines program as they seek technologies to reduce pollutants in similar wastewater streams from similar industrial processes. Similarly, information from issued NPDES permits containing the more stringent water quality-based limits— which may lead a facility to apply more advanced treatment technologies—could suggest the potential for improved reductions. Further, information in fact sheets prepared by the permitting authority could also furnish information on pollutants or technologies that could help EPA identify new technologies for use in effluent guidelines.

How’s that glass of water taste now?

Pingback: Low carb bbq sauce recipe diet coke

Pingback: keto ice cream erythritol

Pingback: sauerkraut and pork on new year's day

Pingback: who sells Gluten free fried chicken

Pingback: hot cross bun easy recipe

Pingback: hot cross bun recipe no yeast

Pingback: broccoli Cheddar soup in slow cooker

Pingback: Gluten Free Fried Chicken

Pingback: Cauliflower Potato Salad

Pingback: breakfast sausage bad for you

Pingback: beef liver vs calf liver

Pingback: Hazelnut Cookies

Pingback: broccoli cheddar soup thick

Pingback: horchata coffee

Pingback: jammie dodger milkshake recipe

Pingback: swirl yeast bread

Pingback: no bake sugar free cheesecake

Pingback: Hazelnut cookies paleo

Pingback: Hazelnut Cookies Recipe

Pingback: aspic beef

Pingback: russian tea cake christmas Cookies

Pingback: hot cross bun cross

Pingback: no tuna casserole

Pingback: braised pork tacos

Pingback: for gluten free cheesecake recipe

Pingback: Homemade granola healthy low fat

Pingback: aspic kabaret

Pingback: broccoli cheddar soup mini pies

Pingback: cloud bread opskrift

Pingback: Healthy recipes for pizza

Pingback: cinnamon swirl donut bread

Pingback: hot cross buns xantilicious

Pingback: how many broccoli cheddar Soup have

Pingback: Hot Cross Bun Recipe

Pingback: gluten free fried chicken kc

Pingback: almond flour gingerbread

Pingback: breakfast sausage without casing

Pingback: breakfast sausage and peppers

Pingback: when sausage recipe instant pot

Pingback: garlic bread tastes like fish

Pingback: stuffed cabbage keto Diet

Pingback: Cauliflower Rice

Pingback: carbonara recipe raw egg

Pingback: salsa verde on steak

Pingback: are keto penut butter Cookies almond flour

Pingback: caprese salad

Pingback: chocolate banana bread marbled

Pingback: chocolate banana bread cooking light

Pingback: lasagna with cauliflower instead of noodles

Pingback: Cauliflower Lasagna recipe