NJ Gets Poor Marks For Teaching The History Of Reconstruction

Content of State Curriculum Standards Described As “Dreadful”

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ ~~~ William Faulkner

I just read a very interesting news story about a Report by the Zinn Education Project on the teaching of the history of the Reconstruction period.

Being an increasingly dedicated reader of US history and a huge fan of namesake Howard Zinn, of course I thought I’d read it, see:

Connecting the past to the present, a major theme of the Report is that the historical legacy of Reconstruction lives on in today’s controversies:

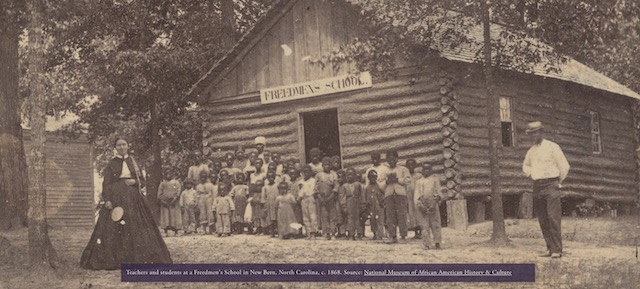

Even as ongoing crises with obvious links to the Reconstruction era continue to reinforce its significance today, most people living in the United States know shockingly little about the policies, people, conflicts, and ideas that shaped Reconstruction and its aftermath.

The Report included a 50 State Assessments on Teaching Reconstruction, so of course I checked that out to see how NJ was doing.

Not so good.

Coverage of Reconstruction is mandated in New Jersey as all districts are required by the state law (Amistad Commission) to “incorporate the information regarding the contributions of African Americans to our country in an appropriate place in the curriculum of elementary and secondary school students.” Unfortunately, this has not yet impacted New Jersey state standards: the coverage of Reconstruction is partial, and their content is dreadful. Students are supposed to learn about Reconstruction first by the end of grade 8 and then again by the end of grade 12. The New Jersey Department of Education adopted new state standards in 2020

The NJ State assessment is preceded by a “reconstruction vignette”, illustrating racism at the Jersey shore.

Of course, Faulkner was right, the past isn’t even past. As the Report documents, what we refer to today as the “beach access” debate was overtly racist back during Reconstruction:

During Reconstruction, New Jersey vacation destinations drew white and Black visitors alike. Many white tourists opposed sharing spaces of leisure with Black patrons and, in the 1880s, some local officials tried to implement segregated facilities and vacation times. In a June 29, 1887, article from The Sun, excerpted here, the author described white outrage at the idea and practice of Black recreation in Asbury Park.

Here’s the “vignette”, what the Asbury Park newspapers were writing at the time:

Mr. Bradley, the founder of Asbury Park, has been moved to protest against what he calls the monopolizing of the seats by these colored sojourners, who, in their turn, have held a meeting to denounce him for undertaking to interfere with their rights. Of course if the seats are provided for the public, the colored people have as much right to them as the white people, so long as they conduct themselves properly. First come first served must be the rule, and whoever finds an empty seat is at liberty to take it, whatever his complexion. Nor even if they are private property is it possible to make any reasonable discrimination against their use by decent colored people in a place like Asbury Park. Yet it seems that the white visitors, even when they are fellow Methodists, are outraged when they find the privileges of the beach largely enjoyed by the colored visitors. They are willing that they should get food for their souls at the camp meetings, and are not averse to employing them as servants, but they do not want to sit by them on the board walk.

NJ’s racist history is blatant and shameful – and the historical echoes still redound to today’s more subtle controversies on beach access:

Many of those families don’t have the time or resources to drive all the way down to Loveladies – (and does public transportation even go there?) where they are not wanted and are actively excluded by those offensive “Private Property – No Beach Access” signs on almost every beachfront property.

Those are the people I was thinking about when I said that the “No Public Acccess” signs along LBI reminded me of the “white’s only” signs of the South.

In case anyone felt that remark was over the top, “played the race card”, or was used as a metaphor, think again.

The signs fit within a culture and a social system of de facto racial and income segregation – including of shore housing and beaches, where the facts are so easily observable.

Those signs are posted with the same racist and exclusionary motives by the property owners.

And they have the same discriminatory on the ground consequences.

Tim Dillingham’s “separate but unequal” comment, about some people densely packed onto beaches while others enjoy a more secluded beach, was accurate and apt – not a metaphor.

That reality is no accident, but the result of racist systems and individual racism.

I am not trivializing racism by equating the effects of historical racism against blacks with beach access.

But yes, gaining access to beaches at Loveladies is like access to drinking water fountains in George Wallace’s pre-civil rights south.

Here’s the full NJ State assessment:

Assessment

Overall, New Jersey’s standards on Reconstruction are insufficient. Though the standards touch on the politics and policies of Reconstruction, they do little to engage with the experiences of Black people during the period, especially their struggles to secure their freedom and autonomy. This is particularly troubling considering the state mandate for schools to teach the “contributions of African Americans to our country.”

In both grade levels in which it is taught, Reconstruction is presented as a political project focused on reunifying the nation after the Civil War that was opposed by white Southerners for complicated reasons. At the high school level, standards focusing on resistance to Reconstruction often equate “Southerners” with “white Southerners” and conceal the efforts and achievements of African Americans who also lived in the South. Missing from this narrative is any mention of Black people’s efforts to gain political and economic equality and independence or the violent efforts by the KKK and other white supremacist terrorists to reinscribe racial hierarchies. Also missing is any discussion of the positive and negative legacies of Reconstruction, though the Reconstruction Amendments are mentioned and could provide a jumping off point for such discussion.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In Jan. 2021, Gov. Phil Murphy signed into law S1028, allocating the Amistad Commission in the Department of Education but independent of the department’s control. The law “requires public schools to include instruction on accomplishments and contributions of African Americans to American society.” It delineates the Amistad Commission’s role in distributing educational materials to educators, monitoring and assessing their inclusion in New Jersey’s education system, and otherwise supporting teaching of “the African slave trade, slavery in America, the vestiges of slavery in this country and the contributions of African Americans to our society.” Among these efforts, the commission has sponsored an interactive curriculum with resources for teaching social studies.

In Nov. 2021, Senate Republicans introduced S4166, a bill designed to ban “critical race theory” and “issue advocacy” from classrooms. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills may have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction. Others expressed their commitment to continue to teach honestly about U.S. history and signed the Zinn Education Project pledge to teach truth. For example, Irvington elementary school teacher Sundjata Sekou wrote, “If teaching about racism, systemic oppression, or anti-Blackness becomes illegal in New Jersey classrooms, I will purposely break that law once an hour Mondays to Thursdays and twice an hour on Fridays!”